The power of people

The sudden collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 followed shortly thereafter by the entire Iron Curtain came as no real surprise to me, and I was not alone. This is not some idle boast with 20/20 hindsight. For a couple of years prior already, the pressure had been mounting on this monolithic razor blade cutting the world in two. It was overly ripe for the fall.

I had been to East Germany several times, birthplace of my now ex-wife, and home to her huge tribe of relatives (her grandmother had married a widower with three children and had then had three of her own with him, who all, amazingly, survived World War Two, if I remember correctly). I had had long conversations with people there, read the local papers, which pretended that everything was fine and all bad things came from the West. Every encounter with an East German involved a liturgy of complaints about the absence of goods … not money. Things. One of my wife’s cousins couldn’t find a replacement car door, for example, because the Five-Year Plan that had been agreed to around then didn’t include passenger doors for the Trabants that year. Another cried after seeing all the East-German wares like those blue polka-dotted Bürgl earthenware cups and the famous “smoke” figures from the Vogtland region being sold at a Christmas market in Frankfurt on the Main in the west. Those goods were not available drüben, over there, at home, in East Germany

Fulfilling shopping experiences were not the only problem. A friend had been in the NVA (the National People’s Army) and reported driving around drunken officers all day in decrepit equipment. And you could see the degraded barracks, the quiet rejection of Russia and things Russian — most people dislike occupiers, regardless, so don’t think this was just “Communism.” People who grew up learning Russian in school hardly speak a word anymore or refuse to. At any rate, all of what I saw contradicted the apocalyptic vision of ultra-powerful Eastern Hordes often referenced in western media with glee and with proof by grainy black and white photos.

Most revealing, perhaps, was a simple conversation, during which I and my interlocutor compared east and west, a very frequent and productive topic. I casually referred to where I lived as “back in Germany” (bei uns in Deutschland). She interrupted me: “This is also Germany.” In that instant, I realized that Bismarck’s claim that Germany would need a civil war once a century to stay united was no longer applicable. This was a unified country with an impenetrable and cruelly ridiculous border running through it. Impenetrable, but not permanent. Absurdity can only go so far.

One just had to hope that a war would not be necessary to break down that wall…

-

The Wall… what’s left of it -

The Wall then: keeping them in and out

A bubble was growing in East Germany, that was for sure, a quiet, unspectacular one. A bigger one was beginning to bulge elsewhere, however, namely Hungary, and thanks to my first book contract with APA Guides, I was able to drive there often as a Mr. Nice Guy writing about travel and culture, essentially harmless stuff for the over-political Communists…

The Hungarians had been chomping at the bit for a while already. Crippling foreign debt and palpable weariness at the leaden straitjacket imposed by a stuffy, unimaginative squad of corrupt apparatchiks was creating a kind of mental rebellion. Judging from the many freedom-fighting idols who appeared as statues, or on the paper money, it would appear to anyone with a moderate sense of observation that Hungarians liked their freedom, and they didn’t like to be told what to do, and if that is the case, they tended to become ornery and uncooperative. Let me mention Kossuth, Deàk, Ràkoczi, the many poets (Petöfi, Ady, Jozsef…), who are naturally inclined to free thinking, and of course Dozsa György, who led a massive peasant revolt against a corrupt aristocracy and died horribly, in 1514, along with many of his followers. A friend of mine, a simple seamstress out east, could recite the national poet Sàndor Petöfi’s famous “Talpra, Magyar” (On your feet, Magyars) that roused the Hungarians against the Austrians on March 15, 1848. From her mouth, it always sounded suspiciously contemporaneous, and very passionate.

-

Petöfi…. telling the Magyars to get on their feet and fight!

Another snapshot: In August ’88, in a crowded csàrda near Tiszafüred on the Great Puszta, I had jokingly called the waitress “elvtàrs,” which means comrade. She yelled back at me for all to hear: “The only thing red with me is my dress,” which was indeed red.

My contacts in the country were all turning west. I crossed the border five times in ’88 without ever being searched. Unlike my crossings into East Germany, which never took less than three hours. I even wrote to editors in the USA (the big magazines, hoping to get The Scoop) that Hungary was almost out of the East Bloc and the Iron Curtain was now a flimsy, rusting reminder of past failures. I explained why I thought it would happen…. “Dear Mr. Radkai, that is all too speculative” was the standard response. The US media simply loved its cloak-and-daggery East Bloc, with its run-down buildings, barbed wire as a metaphor, the sinister cement posts, so dramatic when displayed in grainy black and white on the broadsheets.

It was not all lucubration. There was some action as well. For example, in late June ’88, a massive demonstration was held in Budapest against the systematization (modernization) project initiated by Ceausescu in neighboring Romania, which would have seriously affected the majority Hungarians in Transylvania (the USA still considered Ceausescu one of the better guys in Eastern Europe). After much sending out, the Berkshire Eagle picked up my report on it, bless their soul. A year later, June 16, 1989, with the Hungarian Democratic Forum as a kind of opposition pool, the country re-buried the “hero” of the 1956 rebellion, Imre Nagy, along with Pal Maléter, Miklos Gimes, Geza Losonczy and Jozsef Szilagyi. An empty coffin was added to represent the thousands of Hungarians who had also perished fighting off the Soviet army. It was a huge demo.

-

The re-burial of Imre Nagy

But lots more was happening. In May 1989, guards were removed from the border, an open invitation to use Hungary as an escape route from other East Bloc countries, especially East Germany. Also, on June 27, Gyula Horn was at the western border to ceremoniously cut open the Iron Curtain (I have a piece of it). In August and September, East German refugees started entering the country, allegedly to go on vacation: Hungary had always been known as “the country for encounters”…. my ex-wife’s family would come to the Balaton in summers to meet their East German relatives. These vacationers now spawned a refugee crisis that ultimately forced the Hungarian government to do the right thing and let them emigrate westward. The trickle became a flood.

A journalist friend of mine from East Germany, Ingrid Heller, kept a diary of her escape with her two teenagers:

Budapest, August 23

We went straight to the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany. We hoped to get some assistance there. But the embassy was closed. All I could see was the locked gates, the bell, and the guard house and Hungarian sentinel. Four youths came up from behind and stormed the bell. As if it were a life saver, I thought. A member of the embassy staff came out and handed us some flyers through the gate. They pointed the way to the Church of the Holy Family in Zugliget district.

We headed to the church. The embassy had set up a kind of emergency space in a garage in back of the church. They were taking the applications for passports. We had hidden passport in the pages of books to avoid being noticed by the East German customs officers.

Then the East German “tourists” started collecting at the West German embassy in Prag like the birds on Hitchcock’s jungle Jim . Soon the Czechs had to relent and let them go. The East Germans at home, meanwhile, were not totally passive. I remember hearing that people wanting to move from Dresden in ’86 were giving the reason as “lack of access to western television,” though I suspect that was apocryphal. But it referred to the fact that western TV signals did not reach the great city on the Elbe, which became known as the “Valley of the Know-Nothings” (Tal der Ahnungslosen). In September ’89, they began to demonstrate, culminating in a huge march in Leipzig. The SED government had no cogent response, and repression was not an option, most probably because the USSR under Gorbachev was no longer prepared to back violence. So, whether leaving the country or marching in the streets, people were “voting with their feet,” was a popular saying.

The Wall falls

But in October ’89, I still had to order a visa to enter East Germany. I was planning an one of those cultural-lifestyle articles for a magazine, this time on Frederic the Great, who had palaces in what was now West Berlin and Potsdam in the East. My visa for multiple crossings was for November 12. So I reserved a train ticket from Munich to Berlin for Nov. 10, giving myself a few days to do research and visit friends in West Berlin – yes, my young readers, there were days when you could work at a human pace, read books, dig deeply into your subjects, and have a real social life with flesh and blood people… I then went back to my daily routines, writing scripts for the Deutsche Welle, reporting, preparing more guide books, and, of course, listening intently to short-wave radio, as was my wont.

-

Waiting for the final crash -

The Havel, once a dividing river

On Thursday, November 9, 1989, I was packing and listening to the news in the evening. There came a really strange report from Dresden. Under pressure, Günther Schabowski, a party secretary, had just suggested that private citizens in East Germany could travel freely to West Germany. It was a somewhat confusing message, which directed people to get emigration visas as usual, and then stating, but permitting private travel abroad with short-term permissions (Die Genehmigungen werden kurzfristig erteilt). History has shown us how precarious the situation really was, even the NVA (the army) was mobilized, which could have produced an unbelievable bloodbath, but the East Germans heard it as permission to cross the border. And after some hesitation, they rushed it, notably in Berlin, while millions of West Germans sat riveted to their TV sets, glued to their radios and newspapers (the good ole days).

By the 10 p.m. news, it was clear that something apocalyptic was under way. East Germans were coming across the border without restrictions. And I stood in my living room listening, packing, mouth open, and suddenly realized there were tears streaming down my face.

On November 10, I took the night train to Berlin. It slinked and slithered through East Germany, slowing down as it was supposed to when passing stations, but never stopping, giving us an almost eerie sight of dusky platforms crowded with East Germans wanting to just go, go, go. Because the second night was the real one. Until then, there was fear that the border would slam shut behind those taking tentative steps west. Or worse, the regime would suddenly crack down on the people who had exposed themselves in an explosion of euphoria.

-

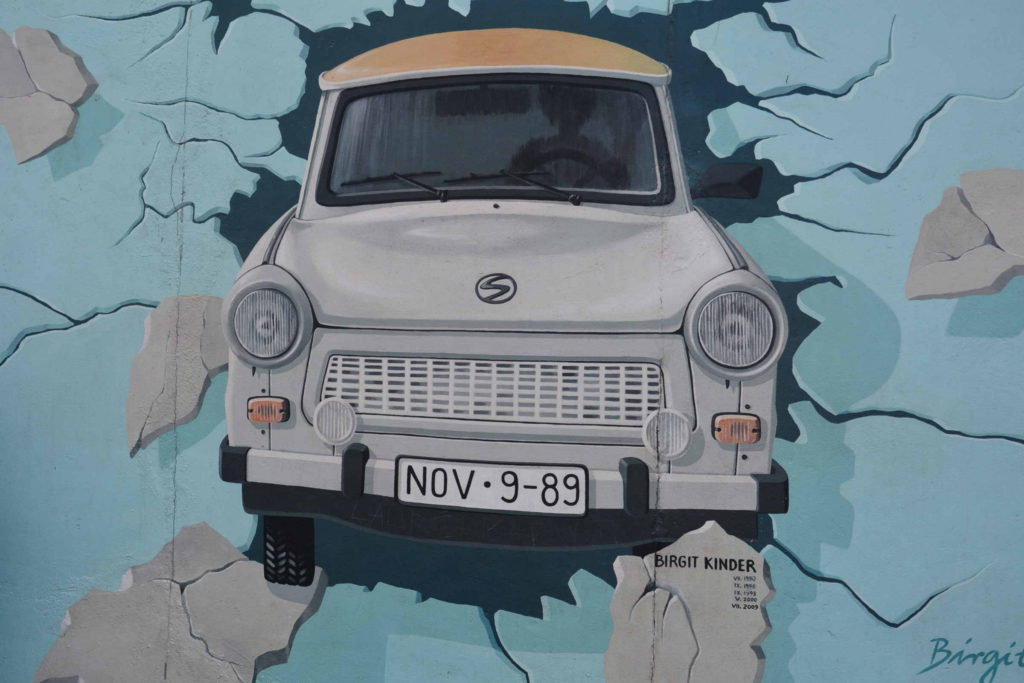

The iconic Trabant crashing through the Wall at the East Side Gallery

Berlin in the morning. It was ice cold. But the sidewalks were bustling, the traffic dense notably with those strange East German cars, the Trabants and the Wartburgs, and the occasional Lada or Dacia (franchises of Fiat and Renault). I deposited by bags at the friends’ place where I was staying and soon joined the thousands of West Berliners and tourists gathered at the Wall. I found a spot not far from the Brandenburg Gate. Climbing onto it was forbidden. It was dangerous, because the other side was essentially a minefield. Many were trying to chip away at it, the so-called Mauerspechte, wall woodpeckers. That, too, was prohibited. In front of me, a Japanese fellow had showed up with a stonemason’s hammer, a huge chisel, gloves, and began whacking away. Bits of painted concrete flew in all directions, the wall shook. I picked up a few pieces. A mounty showed up, confiscated the man’s tool…

East Germans wandered through the city. You could hear them from their dialect. Many wanted bananas, even the KaDeWe had run out, that grandiose department store that was built just to thumb a consumerist nose at the goods-challenged East. I heard that an employee of the KaDeWe had gone into a cheap discounter’s to purchase more bananas … Lines in front of a sex shop… That, too, of course. The East was quite puritanical…

But was this real? It did not feel real at all. It felt more like some magical moment, the kind of über-euphoria that Hollywood likes to conjure with loud music and smiling faces. Some people I spoke to expected the usual cement-heads (it’s German) to bark: “OK, folks, party’s over.”…. That did not happen. The next day, a Sunday, I headed to the Interior Ministry in East Berlin to get my visa. Two hours at Checkpoint Charlie. The Iron Curtain was open one-way only. I changed the statutory 25 deutschmarks for 25 ostmarks.

The ministry was in chaos. Journos running about, officials, pale and wide-eyed, travelers wondering where to go, what to do …. I found the office I needed, got my visa and asked casually: Should I cross the city again, or can I circle the city and go to Potsdam directly…. I had reserved at the Cecilienhof, the famous hotel where Churchill, Truman and Stalin had met in July ’45… “Uh, no you have to go to Gleiwitz.” I didn’t look at my visa. Trudged back to the Checkpoint, bought some chocolate cake on the way for my friends in the west. Waited another two hours. By the time I got through, the cake was mostly eaten.

The rest of the story is available here. What happened then, namely, is quite strange, since I actually ended up in the eastern zone without a visa. In a nutshell: As it turned out, Gleiwitz was the autobahn crossing, and I had requested a train crossing because I was on foot. Secondly, my visa was not a multiple visa, as applied for, but a single crossing.

Let me just add this: When I reached Potsdam thanks to a kindly pensioner who picked me up on the breakdown lane of the autobahn —after changing another 25 deutschmarks into ostmarks — I asked a young woman for directions to the Cecilienhof. She told me, and then asked where I was from. “The USA,” I replied. She spontaneously hugged me and gave me a friendly kiss. It was quite a surprise. So I trudged, exhausted, towards my hotel. On the way I tried to get rid of all those eastern bills. I found an open book shop, and bought several classic novels, books of poetry, some philosophy. When that historically famous palace hotel appeared before me, a thought crossed my mind: The war is finally over, let the peace begin.

Epilog:

The Kohl government rushed to consolidate the openings and bridge the country’s division. The effort was boosted no doubt by the enormous good-will of people in Germany and abroad, the sheer sense of “Yes!” of optimism, of welcome for this new age of international understanding. The People had ultimately won. The bizarre Communist governments fell one after another, some in blood, like Romania, others just crumbled. In 1990, I covered the first elections in Hungary. The Communist Party was running. I spoke to their reps, and they smiled and said: “If we pass the 5% mark, we’ll be happy.” That would have meant at least representation in the parliament. They reached about 3% if I recall…

Yet, as the curtain fell, new walls went up in people’s minds. In Germany, the westerners got suspicious and snarky about the East Germans, especially the Saxons, whose dialect grated on their countrymen’s ears. The easterners created the “Besserwessi,” the western know-it-all ( a play on the word Besserwisser), a kind of carpetbagger, who came and seduced the womenfolk with charm and money (this strange hallucination is not confined to Germany, by the way, it’s something visceral that one finds in xenophobes and racists of all stamp). Then the westerners started speaking of the nebulae, the NEuen BUndesLändern, the new Länder of unified Germany and their bizarre customs. There were also the “Wendehälse,” the European wrynecks, able to turn its head 180 degrees, like the now suddenly former Communist. A cousin of my wife’s, for instance, had been an army officer and had always expressed his anger at “that American” whom he was not allowed to meet, because he was a “holder of secrets.” Suddenly, he wanted to have a beer with me. Then came Ostalgia, nostalgia for the East (Ost). Today, some of those old problems still plague the eastern Länder,

Bit by bit, though, the country did grow back together again. It meant huge investments. There still are differences, and they are always dangerous, because they are visceral. Maybe the jokes were needed to create a bit of excitement and take away some of the raw emotion. But every now and then I will pick up the bit of Wall, or look at my six inches of barbed wire that cut the world in two. And inevitably a tear or two will form as I think of all those people who suffered and continue suffering from the hubris of small-minded men who still use the age-old divide-and-conquer method to maintain their power.