This story is entirely true because I imagined it from beginning to end. Boris Vian (1920–1959) Preamble to L’écume des jours (Froth On The Days)

We all seek a measure of security in a connected, networked world, where corporate identity ensures global monoculturalism at all levels and offers the comfort of familiar space. We can travel the planet without ever really seeing it, enjoy the exact same coffee in Singapore as in New York or Warsaw, buy the same clothes in shops that all look the same, hear the same shallow music with me-me-me lyrics, and even taste the same foods. Our hyper-technology tends to reinforce the uniformity around the globe, creating more safe space, removing all sting and thrill out of the adventure of life. Everything can be seen. And paradoxically, in the flood of images being traded across the globe every second of the day, it’s our imagination that suffers.

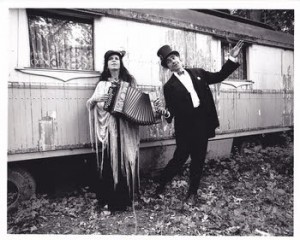

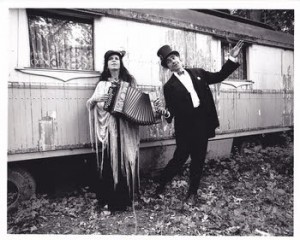

Throughout their lives, puppeteers Tina and Michel Perret-Gentil chose to sally forth into the great unknown without fear of being disconnected. Their particular art of telling stories through their puppets engages the imagination far more than any movie or series of pictures on Instagram or Flickr. Their life and craft dispense metaphors that trigger chains of thoughts and eureka moments and genuinely slake our minds’ thirst for exploration of mystery and for more journeying.

Here’s the story of two very special people living a different life in Geneva.

When Tina was 19, she packed up her bags, took the seeds of her life’s experience from a childhood and youth in the stark, majestic mountains of the Canton of Grisons in eastern Switzerland, and went down into the lowlands to plant them and see what might grow. The year was 1967; in the western world, a new generation of humans was taking its first hesitant steps away from the social and political straitjacket of a more conservative past. Change was in the air, and it was to break into full-fledged rebellion a year later in Paris and other European capitals. Geneva was not yet the pressure-cooker-like, global maelstrom of finance, oil, real-estate speculation and tarnished money it is today, but the presence of the UN and other international organizations already gave it a distinct stamp, a whiff of distant shores, of exoticism that contrasted with the in the quintessential Calvinist petit bourgeoisie of the city. It was a mix lacking elsewhere in the Alpine Republic.

Tina, née Marianna Katharina Casanova, who had learned French and done some secretarial training, had no ambitious plans for life. She just wanted to work at the post office and get a feel for life in a biggish city. “My aunts and my mother had worked at the post office in Obersachsen (her native village), and as a child I would help them deliver telegrams or express mail for pocket money,” she recalls. “I did that for a few months in Geneva but I realized I did not want to be behind a counter all day, I wanted to get out and deliver the mail, and be with the people.” And so her first seedlings withered quickly under the fluorescent assault of reality.

As time passed, however, she came to realize that the post-office job in itself was just a symbol for the determination and self-confidence bequeathed to her from her mother and aunts well before Swiss women even got the right to vote. The Grisons, that large mountainous Canton in Eastern Switzerland with its stark peaks, eight months of snow, where people still speak a derivative of Latin, Rumantsch, boasted particularly traditional values. “They were different from other women,” she says of those powerful women in her life, “they wore more jewels, they wore trousers, they were the first women to ski up there, they all made music, and I got a diatonic accordion for my ninth birthday,” she points out, a touch wistfully. “I had a wonderful childhood up in the mountains, close to nature.”

When I visited Tina the first time to write this article, she was still close to nature. Her home, surrounded by greenery, is unique in and for Geneva, a city plagued by an extreme dearth of lodgings and where rents are astronomical. Almost forty years ago, she and her husband Michel slipped quietly into the nomadic lifestyle of rolling homes “It was not a conscious decision, it just happened,” she says, “but I couldn’t live in a house anymore today. Those poor Romas whom the government was always trying to force into homes, they must have gone crazy.”

They had four trailers, long, dark wooden structures that her life-long companion Michel Perret-Gentil had carefully and skillfully revamped, adding windows, insulation, wood paneling, and the occasional decorative touch. One was for sleeping, one for the office and atelier, there was one for each of their two children, who are now grown up and have children of their own. Her son Jan lived in Uganda for a while, where his wife worked for an NGO. Daughter Anna is in Geneva. For guests or other meetings, Michel put up a large yurt, the tent-like structure of wooden slats covered with felt used mainly in Mongolia.

At the time of the first interview, these homes were located in a garden lot in the Cherpines area of the city, which until May of 2011 had been zoned for agriculture. The two functional homes were placed so the doors face each other. Between the two was a simple picnic table covered in wax cloth and shielded from the rain by a canvas. Often, on warm days and nights, they sit together or with any of their innumerable friends and chat, dream and discuss projects. They are as gentle with the environment as possible, always using biodegradable soaps. The waste from the toilet is compost.

In their five years’ residence at the Cherpines, they had planted a wild garden with roses, some vegetables and herbs, dug a small pond, and even planted a willow, using offshoots from a tree at their previous residence. “Everyday I look at the flowers in the garden, I feel they are inhabited each by their own spirit, and that gives me strength as well and confidence.” These two words return in our conversations over and over again. Strength, confidence.

During our interview, we sat in the kitchen, essentially a wide corridor with a gas stove and an old wood cooking stove used on colder days. The walls are covered in mementoes, pictures, notes, drawings, post-its, the eclectic ephemera of a life on the road and with children. A shelf carries a crowd of strange objects, statuettes and, incongruously, an old shoe. The sheer immediacy of the outdoor takes away any feeling of being inside. It’s spring, and a host of sparrows, blue tits and blackbirds are carrying on a lively conversation. The west wind that brought a light rain is also shaking drops off the trees onto the roof above us and making the nearby highway more audible than usual. The cats come in and out of the open door. The air is rich with spices, herbal teas and espresso and a hint of patchouli, an aromatic anchor in Tina and Michel’s lives.

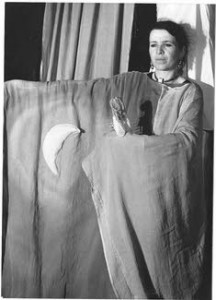

We sit opposite each other. Her eyes are dark aquamarine, almost grey. They take in everything without hunger, as if they could hear. She speaks in clear, emphatic tone, her French has the slight singsong of her native Swiss German, and every move of her long thin arms shakes a parade of bangles. She modulates her voice down to whisper sometimes, or stretches out a syllable beyond its shelf life.

A touch of theater is an occupational hazard: For nearly 38 years, Tina and Michel have been puppeteers, telling stories, singing, accompanying their little wooden actors with all manner of sounds and instruments. As such, they have become an integral part of the cultural scene in Geneva, appearing wherever there is some manifestation or celebration of the stage arts or children to entertain. They also launched a late spring festival called “Dust of the world” (Poussière du Monde), homage to nomadic culture featuring song recitals from the Maghreb or Colombia, or evenings of fairytales. It all takes place in a in the Parc Bernasconi in Geneva. The theater itself is in fact two magnificent concatenated Mongolian yurts, whose cloth walls are supported by slats intricately decorated with arabesques.

It is there, on a Sunday afternoon, that I picked up one of their shows. This one featured their kathputli puppets – a special type of string puppet originating in Rajasthan – enact vignettes from life and legend presented to the scratchy recordings of folk music taken from old 45s. The program opens with two puppet musicians playing… and very quickly you forget the intricate, perfectly timed pas-de-deux of the two puppeteers operating behind a simple anthracite backdrop. Among the more virtuosic scenes is an acrobatic horseman holding a torch on his galloping steed, a little scene featuring a woman who suddenly turns into a man, much to the disappointment of an eager suitor, and our horsemen joisting. It is a far cry from the flash-bang, often violent drama with which the entertainment industry usually tries to hypnotize spectators. But rows of children up front, some surely hardened Wii, Gameboy and TV users, are wide-eyed in fascination, so much so that they begin moving forward and at some point have to be guided back to their place.

Puppeteering is a form of expression in metaphors. The tales always have some didactic or moral goal, or they are reflections of life itself and its sometimes absurd realities. Therein lies the fascination: Like court jesters, the puppeteers can reveal disguised truths for the audience. And after a while, the puppets themselves come alive, a little like Pinocchio, only less schoolmarmish: “The most extraordinary exchange occurs between them and us,” Michel once wrote. “We give them life, and in return they give us the possibility of living. Some are thirty years old. They don’t age. They wait discreetly, always ready for our hands to seize them. The wait is never very long, and when our hands take them it’s not just our hands doing the work, but our hearts are present as well.” By his own admission their creations avoid caricatures, sentimentality, irony and the spectacular, leaving “receptivity and imagination” in Michael’s words.

He is not just venting theory. The puppets are what sparked the couple’s unusual, nomadic lifestyle. They became “the means of transportation for a journey without a goal… Like the horizon, the goal is always escaping me,” he wrote.

That journey began in the early 70s. After the post-office debacle, Tina learned to type and found work at a bank. It was then that she met Michel, a young man with curly hair, opaline-blue eyes, and the wild creative vein of an extramural philosopher. He liked his job washing windows. It gave him time to cultivate and expand his tangled web of thoughts while peering into opulent shops, thoughts that got him thrown out of the military within a week of passing muster. “He was filed as ‘socially not adapted’” Tina says with a broad laugh. “You should have seen his demeanor, plus he had a bunch of psychological reports. But we did have to pay a military tax after that.”

Inspired by friends who had visited India, they put money aside and, in 1971, bought a VW bus and drove to India by road. “It was a magnificent journey,” Tina recalls. There were adventures – such as people shaking their car at night – as they wended their way through the Balkans, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The beauty of discovering the world remains, tinged with the occasional thrill. “Afghanistan was simply marvelous, the people were hospitable, friendly,” she recalls. “Michel and I used to say that no one talked about the country because it was in peace, and look what happened, the Russians, oil, money.” They even stayed with smugglers near the Khyber Pass — “Guns, ammunition and Camel cigarettes! All over the place!” — who offered them an evening of music, dinner, and a night in silk sheets.

They spent nearly a year in India and Nepal discovering a brand new culture. When it came time to return, however, war between India and Pakistan had broken out, so they abandoned their car and flew home with the help of wired funds.

Back in Switzerland, life continued, but their paradigm had shifted. One day they went to see a puppet play directed by a fellow named Michel Politti. It was a classic coup de foudre, love at first sight, when all the disparate parts of life seem to gell into a full-blown affirmation, a single, vibrant “yes!” They wanted to return to India anyway, so  through the Indian Tourist Board they found a center to learn how to make and activate the kathputli puppets of Rajasthan, one of the oldest forms of the art. They gave up their jobs and hit the road again, this time in a small, two-cylinder Ami 6 Citroen station wagon customized for camping. There followed six months of toil, learning to carve, sew and string up the kathputli, and create small, eye-twinkling, moving tales to entertain people.

through the Indian Tourist Board they found a center to learn how to make and activate the kathputli puppets of Rajasthan, one of the oldest forms of the art. They gave up their jobs and hit the road again, this time in a small, two-cylinder Ami 6 Citroen station wagon customized for camping. There followed six months of toil, learning to carve, sew and string up the kathputli, and create small, eye-twinkling, moving tales to entertain people.

Their return to Europe was not auspicious. The car’s engine froze up in Belgrade and they had to leave a large case filled with their freshly made puppets behind to take the train. Nevertheless, back in Geneva, at a little house rented from the city near the airport, they began rebuilding their stock. “We practiced a lot, and a woman saw us and asked if we would like play at the annual meeting of the Swiss puppeteers,” she recalls. “And would you believe it? Suddenly everyone wanted us. People would ask us how much money we wanted, we had no idea.”

The tours began. First to France, then Germany, later to Eastern Europe and England. Soon, they were able to live from puppeteering and decided to buy a big 1947 Saurer bus to save themselves the cost of hotels. Ironically, the vehicle had originally been used by the post office to transport people as well as mail. They travelled about 12,000 miles a year. When the children came (born in 1976 and 1980 respectively) the trips became shorter, or Michel’s mother had to step in as a baby-sitter. Their shows evolved and expanded as new puppets were created and new tales added. Michel had found his calling in the creation of a string of “circuses” with special puppets. In Pécs, Hungary, they won a prize for his “Cirque philosophique,” which combined music (Tina on accordion) and Latin texts. They performed at festivals and in schools, for Christmas and Easter.

Meanwhile, in 1982, the city of Geneva wanted their cheap little house back to turn it into lodgings for flight attendants. Tina and Michel decided to make a deal. Rather than accept alternative accommodation, they asked whether they could use some municipal land and put a second bus on it. The city let them use a plot in the Malagnou section. Soon, real-estate developers started ogling that plot, so they moved to a new place lent by friends, and then when the developers reappeared again, like locusts in neckties, these urban nomads moved again. And again… Each time they came to a new spot, they cleared the grounds, planted gardens, created a paradisiacal human biotope. As the children grew, they added the rolling homes, long, simple structures that had been abandoned by workers or other similar nomads.

Like many gentler flowers, the Cherpines location was long coveted by predators as easy prey. On May 15, 2011, after an acrimonious campaign, the people of Geneva voted to have this rural section of Geneva rezoned for building. It may have been necessary, since the city’s growth needed to be accommodated. Overnight, the price of land exploded and the speculators moved in with deals that were tough to refuse. They offered local property-ownerss staggering sums for their plots. Tina had always maintained a friendly relationship with her landlord. She also kept the plot impeccable, beautifying it with a garden. At the time of the referendum, he was recovering from an operation. Tina visited him as to wish him well and was greeted by a vicious “When are you moving out?” Money talking.

It was time to pack again.

In the six years since the Cherpines were delivered to speculators, not a building has been built. Why should it? You can sit on fairly cheap land while the rest of the city squeezes into small and often dumpy apartments, and the price of the land will just go up. No investments needed, except for some taxes and a few good lawn mowers. The misery of some, make the happiness of others, an old French saying goes. While Genevans waited for more apartments, Tina and Michel had to move. They found a place in the Lignon area. It is not as idyllic, but wherever Tina and Michel “drop anchor,” their space always radiates care, beauty, calm.

January 2017. Outside it’s cold. The damp comes off the river Rhone nearby, it’s like the Erlkönig’s voice. We sit in the warmth generated by the wood stove and talk about the next puppet show. The city is cutting back on funding for artistic pursuits, maybe the deficits will come down, but while economic woes can be corrected, cultural poverty is a downward spiral that eats at the foundations of human society. There is some anger in her voice at the way the world is becoming increasingly polarized. She notes the neighborhood, young people who have chosen to live in their campers to save money, not necessarily idealists. They go to work like everyone else. Then there are the punks, who, she notes, are developing self-sufficiency and engaging in different crafts.

And there is the ever-lengthening past she speaks of as if it was the present. That is the gift of nomads, and it is their essential melancholy. They carry their entire lives in their baggage, in their minds, in their souls, in their homes, tents, on the backs of their camels and horses, or in their old vehicles. Those of us who have moved around a great deal know the value of human beings, of other people and peoples. Our consumer society demands that we fill cellars and attics and try to be reconcile ourselves with an unpredictable future. The nomad collects and keeps mostly weightless stuff around, thoughts, dreams, philosophies, ideas, and sanctifies human to human contact.

Michel sits beside her in the kitchen. His clear blue eyes are opened wide by overarched eyebrows; his look is a mixture of admiration, love, gratitude and amazement. He seems at peace. Those who knew the old Michel speak of his great intellect and ready conversation, his fast mind and love of life. Three years earlier, while packing the stage after a Christmas play, a massive heart attack struck him down. He recovered, essentially, but death’s had struck and its claws raked a part of his mind, taking his treasure of thoughts, his memories and many puppet adventures away forever. Today, he handles the puppets literally by heart, which was always his way. He is a man of the heart, friendly, resolute, creative and a touch mysterious, without being obscure.

Wherever Tina and Michel go, they are approached by acquaintances, friends, admirers. It’s more than just the attraction of the theater. It is the single-mindedness with which they lead their lives and their belief in the importance of the human creative impulse and the power of the individual. Michel came up with a clever, double-edged name for them, “des anges heureux,” (happy angels), which is almost a homonym for “dangeureux” (dangerous).

After our first interview, still in the Cherpines, she took me back to my car back. On the way, she showed me the lovingly tended garden. She is a long, lithe woman, with stunning poise. Her hair is always pulled back in two thin braids that reach almost to her knees. At 62, she moves with the grace of a ballet dancer, be that while walking through the market shopping, receiving gifts, or giving life to the puppets. And the rhythmic sound of a tabla, or djembe, a tombak or any other live percussion will set off a languorous swaying dance like that of a field of wheat caressed by a breeze. The beauty of her being radiates from an inextinguishable inner fire. At night a lighted candle always flickers near their home, “to signal that we are here, we are still burning,” she smiles. As I drove away in the luke-warm spring drizzle, I could see their home in the rear-view mirror and another quote of hers echoed in my ears:

“We are on wheels. When we go, we will leave no traces.”