A brief review and shout-out to a film never seen before, because its world première was given the day after the official closing of the great Locarno Film Festival, which is held every summer on the Piazza Grande of this traditional hub of Swiss tourism.

Asino Vola (Fly, Donkey) was screened on the Sunday night August 16, following the Festival’s official closing. The day had taunted the region with rain, but ultimately delivered a dry and slightly chilly, starry night with no moon, a perfect finale to one of the world’s great film bacchanals. It was billed as a children’s film, so obviously Locarno’s Piazza Grande was filled to the brim mostly, it seemed, with the young and their parents. This was not a children’s movie only, however, it was more like a cockeyed fairytale, ageless, a touch magical, humorous, heartwarming.

Asino Vola (Fly, Donkey) was screened on the Sunday night August 16, following the Festival’s official closing. The day had taunted the region with rain, but ultimately delivered a dry and slightly chilly, starry night with no moon, a perfect finale to one of the world’s great film bacchanals. It was billed as a children’s film, so obviously Locarno’s Piazza Grande was filled to the brim mostly, it seemed, with the young and their parents. This was not a children’s movie only, however, it was more like a cockeyed fairytale, ageless, a touch magical, humorous, heartwarming.

The story of Asino vola is quickly told: A little boy, Maurizio (Francesco Tramontana), seven years old, living in a dusty Sicilian backwater, dreams of becoming a musician and makes good thanks to a drum that he learns by proxy, since the bandleader had assigned him to a flugelhorn, which his parents simply cannot afford. As in all good stories of success, the path to the goal is really what counts, and in Maurizio’s case it is not all smooth going. So much can be expected of a movie.

Obviously, no spoiler alert needed: Right from the start, the viewer is thrust into the culmination of Maurizio’s wishes, with the spicy details to come during the next 75 minutes or so. Maurizio has become a conductor and is seen entering the Scala for a rendering of Verdi’s Ernani, which, the audience learns later, has a very difficult drum part. He is not alone in the frame: on the pillar outside the opera house and then in his dressing room, he finds obnoxious chickens chattering in plain Italian. These beasts are the link to his unusual childhood. One of them lays an egg, chides him, and then tells him his mother, Rosa (Silvia Gallerano) will kill him. These chickens are just the opening gambit in the game of Maurizio’s life. Once we accept them, we will accept anything.

Maurizio, we soon find out, grew up in considerable material poverty, a world portrayed without sentiment or lugubrious drama. He lives with his parents and a rather taciturn grandmother in a jerrybuilt house with a corrugated iron roof. The ara is something of a ghetto for the disenfranchised. Next door is a bunch of gypsies, real characters, superbly cast – like everyone in the film – dark-skinned, mustachioed, curly-haired men, speaking the local dialect (a reminiscence of Visconti’s Terra Trema?) that the producers carefully subtitle with graphics in speech balloons. They live by their wits and recycling junk, it appears.

Maurizio has his playground, a dried-up riverbed that serves as an improvised dump. He is a creative boy, able with his hands and imaginative. He has turned the wreck of an old Fiat 500 into a little cabin, uses engine grease as “Indian” war paint, and hunts for treasures in his unofficial turf.

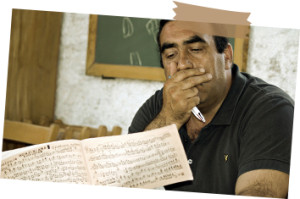

It’s in this somewhat devastated setting that he develops a deep attachment to music, thanks to the local bandleader, Maestro Angelo (Antonello Pensabene), who brings together old and young alike for practice. The band is both entertainment and a way to make some headway up the social ladder.

Lacking money for the flugelhorn he is supposed to learn, he ultimately chooses the drum, which almost eludes him as well. In the end, given myriad obstacles to overcome, he learns to play an, we are given to believe, ultimately makes music his life’s profession. But he succeeds with the collusion of a host of extraordinary partners, including the old donkey Moses, who advises him wisely, and the irksome chickens, allies of his reluctant mother whose opposition to this impractical activity seems to fire up Maurizio’s will rather than discourage him. In one superb scene, N’Giulina, Rosa’s favorite chicken, pretends to have been killed at the hands of Maurizio, just to get him punished.

Asino vola finds its roots in neo-realism, though any potential heaviness is leavened by the lively imagination of the child protagonist who, as an adult, reminisces off-screen without too much redacting. Francesco Tramontana, a gangly little boy with an upturned nose, renders Maurizio brilliantly. His natural shyness, which the public got to see live before the showing, becomes a vital asset in the film. Maurizio’s dark eyes and delicate face betray all the emotions that his voice barely has a chance to express, given the sparse dialogue.

Directors Marcello Fonte and Paolo Tripodi avoid the searching, surgical camera in favor of a scanning approach. The lives and actions of these characters unfold before our eyes as if we were all flies on the wall. We are privy to the worn-out mother with her natural sensuality still intact trying to keep a semblance of dignity in a dismal kitchen, to the old bandleader, whose voice cracked on the death of his composer son, unable to control his demons, to the gentleness and politeness of the younger bandleader, the portly Maestro Angelo, and many more. What Maurizio’s father does is never clear, but “odd jobs” describes it best. As already mentioned, the script is terse and natural, without any speeches or long moral hectoring. The audience is generously given time and space to revel in these multifaceted people, in a story that leaves much open to interpretation. It’s a relief, after the tyranny of pseudo-excitement used by many filmmakers, notably those coming under the influence of Hollywood’s formula.

Asino vola moves along at a fair clip thanks to these well-defined characters and their all-to-human quirks. The rhythm is never disturbed by sudden and dramatic coup de theatres. In fact, any expectations we might have from our conditioning appears to be purposely dashed. When Maurizio opens a suitcase unceremoniously dumped in his playing fields, he does not find it is filled with money, it does not contain a much-needed snare drum, it does not bring him closure.

So, he stuffs a fur coat into it, an iron and sundry tidbits, and schleps it back to his mother. In a more subtle moment, when Maestro Angelo visits Rosa to speak about Maurizio’s learning, he arrives in a well-kept VW beetle and is met by the gypsies, who compliment him on his vehicle. When he emerges from Rosa’s ramshackle home, the camera scrupulously avoids showing the car. Are the hubcaps gone? The tail lights? A door? The answer is no. Everything is normal, the curiosity of the neighbors was nothing more than plain curiosity.

In fact, there is nothing spectacular about Asino vola, no slam dunks, no violence, no guns, no knifings, no titillation and instant gratification, no sophomoric prurience. The film lives of its well-shaped characters and outstanding cast, its naturalistic photography, the stark location that one can almost smell, and the dedicated soundtrack, which is in perfect harmony with the image, a touch folksy, melancholic at times.

As Maurizio’s quest evolves, he is not cast into some horrible Manichean battle of good versus evil, of intense competition, of heroes and bad guys. Asino vola is the opposite of a puritanical Disneyesque tale of rags to riches through blood, sweat, toil and tears, with everyone happy at the end and the bad guys dead or in prison. Everyone in this film is in his or her own way a hero, and things do not conspire against Maurizio – except, perhaps, those irritating chickens, but they are in a cage mostly – they conspire to help him: When Maurizio’s drum needs fixing, the gypsies try to do it the way they fix cars, with lots of discussion in heavy dialect and the corresponding results; another young boy with experience tries to teach Maurizio how to blow in a trumpet; his father does a magnificent job hoeing a garden in exchange for lessons for his son, and when the teacher looks at it admiringly and suggests that it’s more than just a lesson, dad remarks that that is all he can do. The silences in the exchange allow us to speculate for a few moments about their thoughts. But it is only speculation. Even the donkey, Moses, pitches in with wise advice. In this story, solidarity makes the world go round.

Final analysis

All this gives Aniso vola its indelible charm and leaves one satisfied at the end. It even covers up the flaws, like the near-clichés of the over-excitable old bandleader, for instance, or the somewhat construed ending with adult Maurizio conducting (well, that could be more realistic!) a chicken sitting on a drum. If you want a tale of Rugged Individualism, full of sound and fury disguising a banal story, with lots of manipulative music to accompany the storyline to make sure you never stray from the meaning of the film, then avoid Asino vola. If, on the other hand, you want a well told tale that plays the full register of your emotions, that paints a world in myriad crazy colors, will give you food for thought and is polite enough to let you draw your own conclusions, then hop onto the flying donkey for a ride. And bring your kids.